As I am in the process of offering my new group coaching program “Boundaries for BIPOC”, a 6-week group container for Black, Indigenous, and/or People of Color (BIPOC) looking to set and hold boundaries, I’ve been thinking about the different contexts we consider boundaries in our lives.

According to Nedra Glover Tawwab, the author of Set Boundaries, Find Peace, there are 6 types of boundaries: physical, sexual, intellectual, emotional, material, and time - with 5 different contexts we might encounter them: family, work, romance, friendships, and technology.

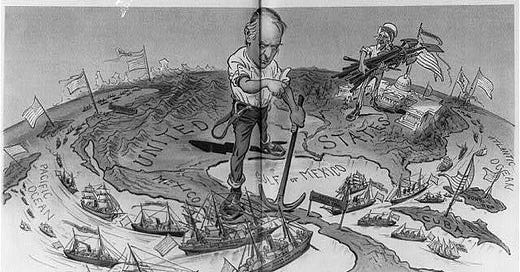

I wanted to take this a step further into the macrocontext of these contexts which ultimately are the systems we live, including U.S. empire. What goes along with U.S. empire is colonization and capitalism, massive wealth accumulation and massive wealth (and health) disparities. A land that allows healthcare and utilities to be privatized. And one that has an extractive and detached relationship to the land, juxtaposed with Indigenous peoples who see the land as kin.

So this makes me ask the question: does U.S empire and its associates have boundaries? Or walls?

First, I think it’s important to define these terms. Boundaries, according to Tawwab, are defined as “expectations and needs that help you feel safe and comfortable in relationships.” On the other hand, “[w]alls are rigid boundaries through which you intend to protect yourself by keeping people out. By offering very little flexibility in your boundaries, you keep out both harmful and positive things and people. Walls are an unhealthy way of protecting yourself from abusive or dangerous situations, as they are rigid and indiscriminate,” Tawwab writes.

Basically, walls keep people out and boundaries show how you can have a relationship with someone.

Does the U.S. put up boundaries or walls?

While it’s not exactly the same, we can apply these definitions to how nations relate to each other, while not forgetting how power and control are critical factors.

Given that both Obama and Trump built a literal wall at the U.S.-Mexico border makes me think the latter for the United States. This wall was intended to keep people out, people who were deemed to be “dangerous”, instead of recognizing the deep history of Mexican immigration to the United States.

Walls often avoid issues and gaslight others into thinking they are the problem.

Is the U.S. embargo on Cuba a boundary or a wall? Is not allowing trade from the U.S. to Cuba a way to have a better relationship and encourage safety, or is it a way to punish a population by withholding food, clean water, and medicine from them? Is Cuba abusive or does the power of U.S. empire make us think so?

What about redlining? What about blockbusting? Who are we keeping out and who are we keeping in? And is there a more relational approach that addresses the “problems” we feel make it necessary to employ these tactics?

It seems that creating these walls also makes someone an “American” or a “patriot” - people who enjoy claiming the United States is the greatest nation on Earth. By deeming we are the best, someone has to be the worst, or at least worse. And in order to be the best, relationships are destroyed at worst or politicized at best, land is exploited, and labor must be made cheap.

The U.S. military apparatus is itself the greatest tool of U.S. empire. One example of this is the United States’ relationship with Afghanistan, a country where we had a close friendship with Osama bin Laden, once providing over $3 billion in military training and weapons to him and the Afghan mujahideen before deciding he was an enemy. A brilliant, dear friend of mine, scholar on Islamophobia, and author, Dr. Nazia Kazi, writes about this and the other connections to U.S. empire’s global reach, including in the Middle East, in her book Islamophobia, Race, and Global Politics. She writes:

Iraq’s history is marked by meddling by foreign powers (British and American, primarily)—meddling that involved disrupting democratic movements, establishing dictatorships, and arming unsavory characters, in large part to enrich themselves (for instance, through the extraction of oil wealth). When the United States was reckoning with the “threat” of Iranian power in the Middle East, Iraq (and Saddam Hussein specifically) had served as a key ally to the United States. Hussein received handy support, even when acting as a brutal dictator, when he was protecting US interests in the region. Eventually, though, he would stop acting on behalf of the United States. In 1991 the United States went to war with Iraq after Hussein ordered an invasion of Kuwait. Two separate UN humanitarian coordinators resigned from the post after declaring that the civilian costs of US and British bombing campaigns in Iraq were unconscionable. What followed that war was years of sanctions that left a whole generation of Iraqis to suffer malnutrition, hunger, and poverty. While President Clinton officially issued these sanctions as a punishment for Saddam Hussein, their impact was on ordinary Iraqis. When then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright appeared on a 60 Minutes news segment in 1996, where Lesley Stahl asked about the Iraq sanctions, “We have heard that half a million children have died. That’s more children than died in Hiroshima. Is the price worth it?” Albright replied, “It is a hard choice, but we think the price is worth it.”

My students are stunned to learn of the close relationship that existed between the United States and the very Saddam Hussein who was later dubbed the ultimate threat to US stability. This history—of alliances, destabilizations, sanctions, and invasions—has left an Iraq so devastated, so destabilized, that it seems almost natural that a group like ISIS should form. ISIS took hold in the midst of a toppled Iraqi state and the desperation of a population that had lived through far too much trauma. Today, many in the United States have a vague understanding of ISIS as the “bad guy” in the region, but very little historical understanding about how this militant Sunni Muslim group rose to power on the global stage.

The borders of Iraq, Afghanistan, and the many places U.S. empire wants to mold in its hands were and are in service to U.S. interests. Those “relationships” were about resources, and when these resources were no longer available, sanctions or embargoes or some type of punishment get enforced. Sanctions themselves are defined as “an action that is taken or an order that is given to force a country to obey international laws by limiting or stopping trade with that country, by not allowing economic aid for that country”, and, ultimately, it is about control and power. When an abusive person wants to control the person they abuse, they put up a wall, withhold their attention, and gaslight in order to have power. Is this much different?

I’ve only given a few examples of the gravity of punishment and control exercised by the United States. Asking if the U.S. puts up boundaries or walls was probably a bit leading of me, but when American exceptionalism only desires relationships based in supremacy, not in reciprocity, which harms the people within and outside the country, it’s hard not to be leading.

Indigenous erasure and sustainability

Indigenous erasure within the U.S. is another example of figuratively and literally bulldozing land to create borders that served the state rather than the peoples who lived on it, the peoples who knew how to relate to it, and the peoples who granted it safety, not extraction. It is not a made up Thanksgiving story of happy and communal relationships.

As Howard Zinn said in A People’s History of the United States, “Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals the fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.”

The binaries Zinn speaks of—masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, etc—don’t allow much room for boundaries—of knowing your values and taking responsibility for them while loving others in a way where you can also love yourself. Colonization and U.S. empire is dominance, spite, and control, not a mutual love fest.

And as Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz said in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, “Everything in US history is about the land—who oversaw and cultivated it, fished its waters, maintained its wildlife; who invaded and stole it; how it became a commodity (‘real estate’) broken into pieces to be bought and sold on the market.”

It’s clear that the way U.S. land is now stewarded has rapidly increased a global climate crisis, whether it is through resource extraction, continuing wars in service to American imperialism, food insecurity, and more than I can even list here.

Speaking of climate change, I often hear about “sustainability” when it comes to the topic of the environment. It’s become a sort of buzzword that has validity and, like most things, gets co-opted by capitalism. Sustainability is about how the environment and humans can co-exist—about our relationship and interdependence with each other. It’s about creating personal and community boundaries in order to honor what the land gives us, be it water and land use, how resources are distributed, and more. But this is not a personal responsibility. Sustainability is wholly possible when the land can be governed and guided in a way where policies and consequences are created to extend the life of the land, nature, and humanity. Or it can be governed and guided in a way where loopholes are made for corporations and pushing for global renewable resources is an uphill battle—this seems to be the choice made by empire, capitalism, and white supremacy culture. The wall that has been put up to prevent true sustainability is fierce and designed to minimally yield, and only to the structures that created it, merely changing its shape or material but, nonetheless, standing mighty and tall.

Systemic walls trickle down

Just like the effects of colonization, empire, slavery, war, and poverty are transmitted to future generations through epigenetics and intergenerational trauma, the historical walls that have been built by U.S. empire, colonization, and capitalism, trickle down into our everyday lives. It looks like sacrificing our bodies and health for the sake of a corporation or institution, labeling others as “bad” so we can be “good”, reinforcing toxic codependent behaviors by staying in harmful relationships, and being more concerned with someone else’s sustainability while we don’t even know who we are.

So who are we?

We are individuals, in a collective, living in an ecosystem during the Anthropocene. Boundaries aren’t easy, but do they have to be this hard?

Note: Links to books are Nisha’s Bookshop affiliate links

![Illustration shows President McKinley straddling the "Gulf of Mexico" with one foot on the United States and the other on Mexico or Central America, rolling up his sleeves to resume work on the "Proposed Nicaragua Canal"; Uncle Sam, in the background, departs Washington with an armload of tools. Ships line up on both sides of the proposed canal site, waiting to pass through. U.S. flags fly over "Philippines, Hawaii, Alaska, Cuba," [and] "Porto [i.e. Puerto] Rico." Illustration shows President McKinley straddling the "Gulf of Mexico" with one foot on the United States and the other on Mexico or Central America, rolling up his sleeves to resume work on the "Proposed Nicaragua Canal"; Uncle Sam, in the background, departs Washington with an armload of tools. Ships line up on both sides of the proposed canal site, waiting to pass through. U.S. flags fly over "Philippines, Hawaii, Alaska, Cuba," [and] "Porto [i.e. Puerto] Rico."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8002a7ca-f057-4d31-ac1c-09197df72fa8_640x424.jpeg)

Share this post